The ancestral knowledge of indigenous peoples is an ancient heritage that the ancestors have passed on from generation to generation. This wisdom is part of their system and structure of life linked to their spirituality, identity, practices, economy and culture. This was the theme of the panel “Ancestral knowledge: Contributions of indigenous peoples to reduce the impact of climate change”, convened by the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests (AMPB) within the framework of New York Climate Week in New York. The objective of the space was to gather the experiences and experiences of the indigenous communities and peoples of the Mesoamerican region from their ancestral knowledge in favor of the fight against climate change.

The event, held at the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Manhattan, featured:

- Salina Sanou, Deputy Director of IPARD and Regional Director for Africa and Asia at the FSC Indigenous Foundation (Moderator)

- Briseida Iglesias, Delegate of the Coordinator of. Women Territorial Leaders of Mesoamerica – Bundorgan Women’s Network (Guna, Panama)

- Levi Sucre, AMPB Coordinator (Bribri, Costa Rica)

- Sara Omi, President of the Coordinator of Women Territorial Leaders of Mesoamerica (Emberá, Panama)

- Pamela McElwee, Professor in the Department of Human Ecology – School of Environmental Sciences and Biology at Rutgers University, lead author on IPBES

- The panel began with a ceremony led by Briseida Iglesias, Guna sage.

- Salina Sanou called for a return to traditional models that give a central role to indigenous women.

- Briseida Iglesias: “Our grandparents have lived and have maintained these forests, where each animal has its home, as well as the human being. But if we ourselves destroy everyone’s house, what will happen in the future, brothers?”

- Levi Sucre: “There is territorial management, there is forest management, food production from the indigenous worldview. We can teach both agronomists, biologists, foresters.”

- Sara Omi: “Our forest is dying and if it dies we lose identity, we lose worldview, we lose the house that we must ensure for future generations.”

- Pamela McElwee: “The reciprocity between people and nature results in the protection of biodiversity, and now the scientific community wants to include the holders of this knowledge in scientific studies.”

Ancestral knowledge and climate

Indigenous peoples know a lot about climate dynamics, the behavior of biodiversity and natural resources in direct relation to climatic variations. This knowledge and experiences accumulated throughout their existence, are very useful for the management of their productive activities, since they design adequate strategies to solve their subsistence needs as a family and community; as well as to make decisions at a social and cultural level. For indigenous peoples, the loss of forests and the dispossession of their lands constitutes a decrease in their chances of survival, since the forest and the territory constitute their home and provide them with food, medicine, construction materials, firewood, water. and all the material and spiritual elements that ensure the long-term maintenance of community life. Forest degradation brings with it malnutrition, an increase in diseases, dependency, acculturation and, in many cases, emigration and the disappearance of the community itself.

How is the territory perceived from the ancestral knowledge of indigenous peoples?

As part of the ancient heritage and philosophy of the peoples, the territory is a whole and a living entity with its own spirituality and sacred character, which provides security for continued survival, as well as food, clothing, medicine, fuel and all materials necessary for existence. Men and women depend on the forest for the satisfaction of most of their subsistence needs, which is why they must take care of it and love it as life itself.

Currently, the penetration of the market economy has forced local populations to overexploit the forests, which means a serious threat to their livelihood. This is one more anthropic factor that contributes to the climate crisis.

The question then arises, what to do?

And the immediate answer is: it is key and urgent to generate adaptation strategies based on the knowledge of the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica with a gender and intercultural approach, which contribute to promoting social and gender equity, without losing sight of the fact that , in order to guarantee the permanence of this knowledge and knowledge, real recognition must be given to said knowledge, in addition to the fact that it is urgent to guarantee the protection of their rights as subjects of rights and their right to territory.

Indigenous peoples, their territory and their ancestral knowledge cannot continue to be victims of cultural undermining, they are seen as “folklore as well as their knowledge in climate dialogues, thus reducing them to a caricature, a superfluous image, a shell of what It actually constitutes an accumulation of knowledge, practices and traditions that are the expression and life of a deep worldview”, as indicated by the daily digital telegraph of Ecuador.

The indigenous peoples understand that it is not easy from the Western world to try to understand what ancestral knowledge is, since for this they must go through a process of “decolonization of thought”, this will allow them to understand that ancestral knowledge is the expression of a deep and complex worldview, which is far from the conception of the Western world; understand that the knowledge and understanding of this knowledge cannot be given fully through a process of description, analysis and categorization, since the true understanding of ancestral knowledge arises from the experience of that worldview, in which intuition and feeling are intertwine with thought to generate knowledge of the world. This way of ancestral and cultural knowledge of the indigenous communities and peoples of North, South and Mesoamerica, have shown that they are capable not only of protecting and preserving nature, but life itself.

Watch the event recording here:

Living examples of ancestral knowledge in Mesoamerica

K’ax Kol’ system of the Mayan K’iche’ people in the Guatemalan Altiplano

The K’ax K’ol’, means community service in the territory, which implies that women and men must provide a contribution in the care of the forests when they reach the age of majority in the community and the municipality to which they belong. This community service consists of patrolling the boundaries of the territory, monitoring and preventing illegal logging, forest fires, pests and diseases. It should also contribute to the restoration of degraded forests through the establishment of forest nurseries of native seeds and their reforestation using ancestral knowledge according to the lunar cycle.

This ancient practice in the K’iche’ people is a mutualistic relationship between human beings and Mother Nature, because human beings receive services such as water, oxygen, firewood, medicinal plants, food, recreation, among others, from the sacred forests. others. This system has worked for centuries, because in addition, the decisions are agreed upon in the community, for example, when making a forest harvest.

It is important to highlight that the K’ax K’ol’, within the territorial governance is; mandatory and ad honorem, but provides benefits for the common good and reduces environmental degradation.

Cabécar traditional crop system.

Nainu, an ancient food alternative of the Guna peoples of Panama

From its origins, Dule agriculture has been family-based, as evidenced by the Nainu agroforestry system (Castillo, 2013). Family farming is a system that has a close relationship with the environment, culture, community and is practiced obtaining food production for the family.

Its essence is native, indigenous and peasant, because it starts from a harmonious relationship with the environment – Nabgwana (Mother Earth). In this sense, the Nainu agroforestry system implies a number of characteristics about society and production that go far beyond the limits of the Nainu, it is an agroecological practice, as old as the origins of agriculture (Altieri, 1999).

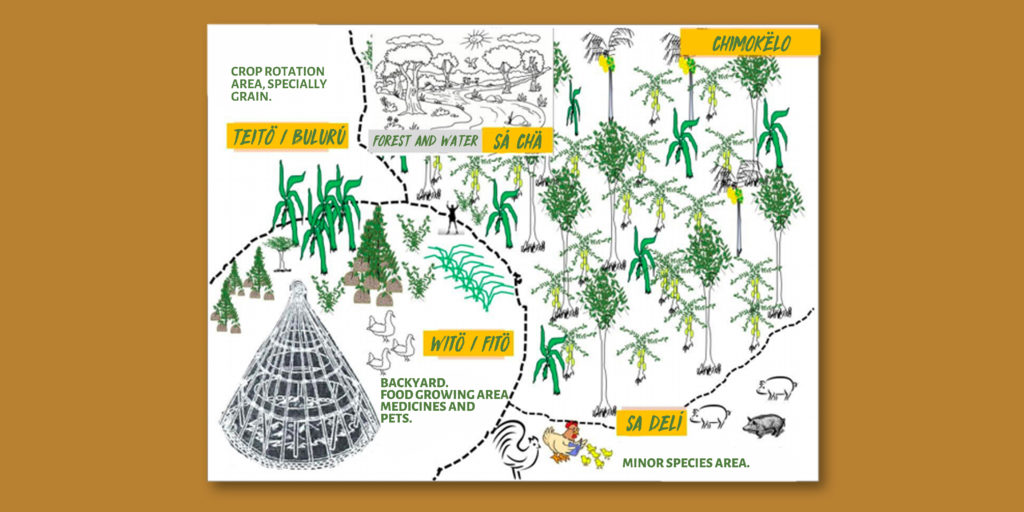

The Dule people visually divide their territory into three parts: 1. Primary Forest, which is the intact forest area; 2. The Secondary Forest, where controlled use and exploitation practices are carried out; 3. The Nainu Forest is the area near the house or near the community. Each one of this area fulfills an essential function in the subsistence of the territory.

The Nainu Forest or system consists of a young forest combined with fruit trees, agricultural and medicinal plants, and backyard animals. It is important to highlight that in this system, the cultivated areas comply with a rotating cycle of land use, when a plot has already been used, it is left to rest for a few years so that the nutrients of the land can be regenerated. “When we cut down a tree or a plant, we ask permission from Mother Earth and the plant, in this way the plant or the tree fulfills its function kindly, because we have their permission to use it. In our culture, trees, land, and plants are living beings”, emphasizes Giuseppe Villalaz, cultural interlocutor of the Guna People.

The NAINU system is an ancestral practice of the Dule people, which allows the population to produce a diversity of food, in harmony with the forests and the land, and at the same time conserving this natural wealth that is still alive. This is what must be understood by sustainability, and not destroy them to obtain fuel and genetically modify them. From this integral context of dule agroecology, it contributes to the reduction of the impacts of climate change, it is an example of resilience and adaptation to climate change based on ecosystems, communities, and agriculture.